Morrison Art Studio Artist Features

Morrison Art Studio’s MFA Studio Assistant, Phuong Nguyen, has been spotlighting artists from varied communities and cultures within the art world. Read more below to learn about the backgrounds and practices of artists from different time periods, art movements, and countries and be sure to check out the links for even more information. Check back as we’ll update this list whenever Phuong has covered a new artist!

There are so many diverse perspectives that make art even more amazing and wonderful and we’re excited to discover, learn and share them with you!

Featured Artists

Click on an artist below to learn more!

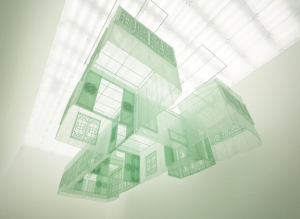

Do Ho Suh

Born in South Korea, Do Ho Suh now lives and works in London. Suh’ experiences as an immigrant fueled his longing for his homeland and complicated his perception of the home. What draws Suh to using fabrics in the first place is the flexibility of the material, allowing a life size sculpture to be folded up and carried around in a regular suitcase (much like our clothes) a metaphor for the memories and emotional attachments that occupied our minds.

The first major fabric sculpture Do Ho Suh completed was Seoul Home, aptly titled since it is modeled after his parents’ home in Seoul, which itself is an exact replica of a traditional Korean scholar’s house in the royal palace complex. Every part of Seoul Home is carefully considered. The light jade color references the color of the ceiling paper used in traditional scholar’s houses that symbolizes the sky or the universe – something larger than oneself. Suh especially sought out seamstresses who specialize in the traditional Korean sewing techniques and craftsmanship in order to learn specific stitches and to make decorative ornaments and details.

Each nook and cranny of the house’s interior is meticulously measured before moving onto preparing the fabrics. When asked about his experience during this process, Suh said: “I was able to discover so many things… [It was] and emotional experience. Often, you’d find a little mark that you did when you were a kid and that brings back all the memories of your childhood, and when you went through that process, the space really became a part of you.”

While Suh meticulously measured and traced every line of his parents’ home, the fabric counterpart is not and cannot be the exact replica. Seoul Home, much like all of his fabric sculptures, utilizes the limitations of the transparent fabrics as ‘building’ materials to emphasize the intangible memories and psychological responses. Seoul Home is always hung high up from the ceiling, with the fabric walls swaying in the air and out of reach of the viewers. The strong gallery lights are diffused when hitting the fabric and create a dream-like quality to the installation. Lastly, every time the piece is shown in a different venue, the new venue’s name is added to the title – a signifier of the piece accumulating its own histories and meanings.

Rosie Lee Tompkins

Rosie Lee Tompkins is the pseudonym of Effie Mae Martin Howard, an incredible African American quilt maker. Born in 1936 to a sharecropping family in rural Arkansas, Tompkins learned the how-to of quilt making from her mother when she was young. Financial hardships forced Tompkins’ mother, as well as other homemakers in the community, to use any available pieces of cloth – from scrap fabrics to old clothes, to make quilts for their families. Perhaps influenced by and learned from her mother’s ingenuity in sourcing materials, Tompkins did not shy away from any material when piecing together her own quilts. She used a wide variety of fabrics, from cotton to velvet and denim. Kitschy printed tablecloths, embroidery patches, sequined fabrics, and crocheted doilies made frequent appearances as well.

Take, for example, this narrative quilt from 1996 that measured 14 feet across. Tompkins used pieces of the US flag, printed dishcloths, parts of a feed sack, embroidery patches, and a mass-produced tapestry of Jesus to literally piece together “the melting pot that is American culture and politics”. (1)

Another one, like this appliqued quilt that Tompkins started in 1968 and finished in 1996, is interpreted to be a celebration of California, her adopted home state. Its surface is adorned with tourist trinkets, embroidered patches, rhinestones, doilies on top of a patchwork of red and floral printed fabrics.

Tompkins’ abstract quilts attract no less attention and love. For instance, this seductive velvet quilt from 1992 grabs viewers’ attention with its vibrant color palette and its irregular patterns of squares and triangles. Tompkins’ formal strengths, in particular her bold usage of colors and forms, are undeniable.

Art critic Roberta Smith concluded her review of Tompkins’ Retrospective at the Berkeley Art Museum with this observation that fully captured the spirit of Tompkins’ work: “[Her quilts] come at us with the force and sophistication of so-called high art, but are more democratic, without any intimidation factor.”

Billie Zangewa

Born in Malawi and raised in Botswana, Billie Zangewa now lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa. Her work depicts scenes of her personal life, usually featuring herself and her son or other family members as they navigate through the mundane, daily tasks1. Through sharing her personal narratives and domestic spaces, Zangewa wants to “demystify” and to recognize the humanity and relatedness of Black women in a way that the global/collective imagination usually does not.

She embraces fabrics as the material and sewing and embroidery as the techniques of choice precisely because of the long-upheld dismissal of them as mere “crafts” and as “women’s work”. Aside from a gentle act of resistance, sewing has a personal importance to Zangewa. Growing up, she has witnessed many sewing groups her mother had hosted in their house2. Women from the neighborhood would congregate to sew and to share their own struggles, to talk it out among like-minded peers. She shared that she could still remember the relief these sewing groups had brought to the members. This experience has left a long-lasting impact on Zangewa, and is depicted in Mood Indigo: a couch occupies much of the center of the composition, with two women sitting side by side, both holding fabric/sewing samples while one of the women hid her face in her hand, looking distressed. Around them, others listened in. It speaks of a safe space, a community for black women all over the world.

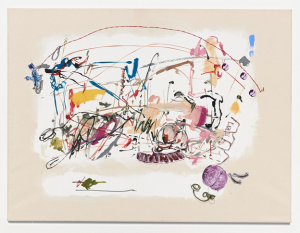

Carmen Neely

A North Carolina native, Carmen Neely received her BFA at UNC – Charlotte in 2012 and her MFA at UNC – Greensboro in 2016. Her painting practice is deeply rooted in abstraction, which she uses as a conceptual framework to discuss broader issues like identity and memory. Each gesture and shape in her paintings takes on its own significance and meaning. Once a single mark catches her eye, she will recreate it using different materials: from embroidered patches to hand-sculpted polymer clay. A lot of times, these marks will reappear across different paintings or transform into large sculptures. Neely uses phrases she’s collected from conversations she’d had to title her paintings – a choice that adds a layer of intimacy and humor to the work.

To engage in abstract, gestural painting in the US is to engage with the long history of the Abstract Expressionist movement and its predominantly white, male practitioners. As a black woman artist, her journey has not been an easy one. In an interview with BLANC Modern Africa on the eve of her first solo exhibition in NYC back in 2017, Neely said: “From the start of my endeavors in abstraction, I have received comments is either ‘surprisingly’ created by a black woman or ‘atypical’ of ‘Black art’.” However, Neely is not one to shy away from that history – she proudly embraces it and claims her space in it. She is one of the six NC-based black artists that make up the NC Black Artists For Liberation Collective whose goal is to fight against systemic racism and calling for institutional change in various cultural and educational organizations statewide.

Learn More

- NC Black Artists’ Collective: NC Black Liberation

- Website: http://carmeneliz.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/carmeneliz/

- Represented by: Jane Lombard Gallery, NYC

- Interview: Carmen Neely – ARTnews.com

- Podcast: Carmen Neely // Jovonna Jones // Trusting the Validity of Diverse Narratives

Maybe we’re just drawing out bad diagrams, 2019. Oil and acrylic on canvas, enamel pin, embroidery. 30 x 40 inches.